9000. Exhibition Introduction

Portrait of Charles William Lambton (‘The Red Boy’)

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

1825

Oil on canvas

The National Gallery, London. Bought with the support of the American Friends of the National Gallery, the Estate of Miss Gillian Cleaver, Art Fund (with a contribution from the Wolfson Foundation), the Al Thani Collection Foundation, The Manny and Brigitta Davidson Charitable Foundation and through private appeal, 2021

NG 6692

© The National Gallery, London

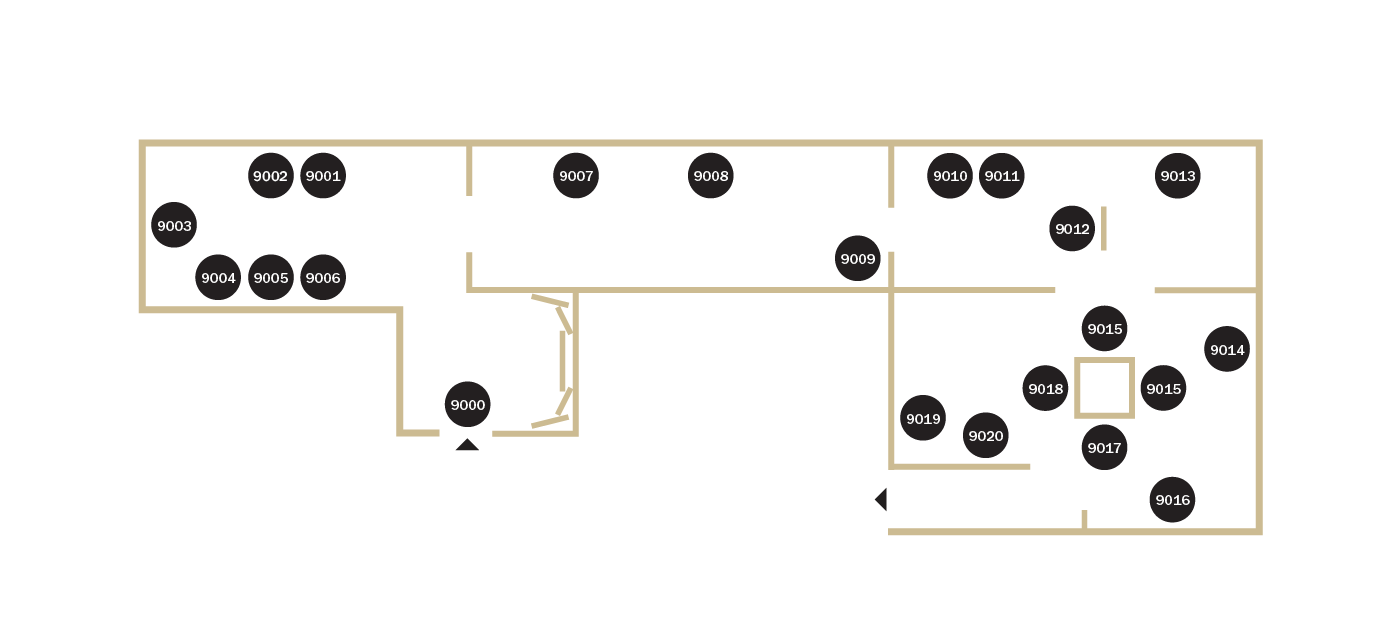

Welcome to the Hong Kong Palace Museum Special Exhibition “Botticelli to Van Gogh: Masterpieces from The National Gallery, London”. We will guide you through four hundred years of Western art history with commentary on twenty paintings. This audio guide introduces you to the major art movements, from the Renaissance to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, as well as the various types and techniques, of Western painting. You will learn how to look at a painting, why it is a masterpiece, who the masters are, and when and where they worked.

9000. Exhibition Introduction

Welcome to the Hong Kong Palace Museum Special Exhibition “Botticelli to Van Gogh: Masterpieces from The National Gallery, London”. We will guide you through four hundred years of Western art history with commentary on twenty paintings. This audio guide introduces you to the major art movements, from the Renaissance to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, as well as the various types and techniques, of Western painting. You will learn how to look at a painting, why it is a masterpiece, who the masters are, and when and where they worked.

9001. Saint Jerome in His Study

Antonello da Messina (active 1456; died 1479)

Saint Jerome in His Study

About 1475

Oil on lime, 45.7 x 36.2cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought, 1894

NG 1418

© The National Gallery, London

This painting by Antonello da Messina is a masterpiece of geometric clarity and descriptive detail. Look at the sandstone entrance arch. Its architectural materials are carefully painted. Each block of the finely jointed stonework is distinct from its neighbour, and each shows the varied mineralogical composition of the sandstone.

Antonello was one of the leading early Renaissance painters of southern Italy. “Renaissance” is a French term that refers to the “rebirth” of interest in classical art and learning, above all from Italy, from the early fourteenth to the mid-sixteenth centuries. The term is used as a stylistic label for the art of these centuries. Artists at the time also learned how to create the illusion of depth on a flat surface—a technique known as mathematical perspective that transformed art of painting in that period. Likewise, artists from the Netherlands developed another transformative technique—oil painting, which allowed them to achieve highly realistic effects.

9001. Saint Jerome in His Study

This painting by Antonello da Messina is a masterpiece of geometric clarity and descriptive detail. Look at the sandstone entrance arch. Its architectural materials are carefully painted. Each block of the finely jointed stonework is distinct from its neighbour, and each shows the varied mineralogical composition of the sandstone.

Antonello was one of the leading early Renaissance painters of southern Italy. “Renaissance” is a French term that refers to the “rebirth” of interest in classical art and learning, above all from Italy, from the early fourteenth to the mid-sixteenth centuries. The term is used as a stylistic label for the art of these centuries. Artists at the time also learned how to create the illusion of depth on a flat surface—a technique known as mathematical perspective that transformed art of painting in that period. Likewise, artists from the Netherlands developed another transformative technique—oil painting, which allowed them to achieve highly realistic effects.

9002. Virgin and Child

Giovanni Bellini (about 1435–1516)

Virgin and Child

Probably 1480–1490

Oil, probably with egg tempera, on poplar, 90.8 x 64.8cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought, 1855

NG 280

© The National Gallery, London

Giovanni Bellini, one of the most influential Venetian painters, was born into the leading dynasty of artists. Perhaps one of the most striking elements in this painting by Bellini is the intense blue of the Virgin’s garment. Bellini painted it using high-quality ultramarine, the most sought-after of all artists’ pigments in Renaissance Venice. Ultramarine is derived from the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli. Lapis lazuli could be found only in one region, which is part of today’s Afghanistan. This vibrant blue of lapis lazuli was imported along the Silk Route and entered Europe by ship.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Republic of Venice was one of the wealthiest and most culturally diverse city states in Europe. It was the first European port on the trading route from the East, which meant that the raw materials artists needed arrive there, and they had the first pick of the finest materials. Venetian artists like Bellini explored naturalism and colour informed by their use of oils and study of northern European paintings.

9002. Virgin and Child

Giovanni Bellini, one of the most influential Venetian painters, was born into the leading dynasty of artists. Perhaps one of the most striking elements in this painting by Bellini is the intense blue of the Virgin’s garment. Bellini painted it using high-quality ultramarine, the most sought-after of all artists’ pigments in Renaissance Venice. Ultramarine is derived from the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli. Lapis lazuli could be found only in one region, which is part of today’s Afghanistan. This vibrant blue of lapis lazuli was imported along the Silk Route and entered Europe by ship.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Republic of Venice was one of the wealthiest and most culturally diverse city states in Europe. It was the first European port on the trading route from the East, which meant that the raw materials artists needed arrive there, and they had the first pick of the finest materials. Venetian artists like Bellini explored naturalism and colour informed by their use of oils and study of northern European paintings.

9003. Three Miracles of Saint Zenobius

Sandro Botticelli (about 1445–1510)

Three Miracles of Saint Zenobius

About 1500

Tempera on wood, 64.8 x 139.7cm

The National Gallery, London. Mond Bequest, 1924

NG 3919

© The National Gallery, London

Sandro Botticelli was one of the most esteemed artists in fifteenth-century Italy. In this panel, he has depicted Florence’s patron saint, the fifth-century bishop Zenobius, performing three miracles in the Piazza di San Pier Maggiore in Florence. The diagonal lines of the steps on both sides of the painting seem to converge towards each other. This compositional device, known as single-point linear perspective, draws our eyes to a focal point in the centre of the composition, where a dramatic scene is taking place.

Renaissance paintings are full of arches and entryways. They invite the viewer into the picture and encourage us to begin a visual journey. Botticelli uses these architectural elements to structure the story and engage us with the events unfolding.

In fifteenth-century Florentine painting, line and composition were of the highest importance. In this panel, Botticelli shows his mastery of both and proves himself one of the greatest painters of his age.

9003. Three Miracles of Saint Zenobius

Sandro Botticelli was one of the most esteemed artists in fifteenth-century Italy. In this panel, he has depicted Florence’s patron saint, the fifth-century bishop Zenobius, performing three miracles in the Piazza di San Pier Maggiore in Florence. The diagonal lines of the steps on both sides of the painting seem to converge towards each other. This compositional device, known as single-point linear perspective, draws our eyes to a focal point in the centre of the composition, where a dramatic scene is taking place.

Renaissance paintings are full of arches and entryways. They invite the viewer into the picture and encourage us to begin a visual journey. Botticelli uses these architectural elements to structure the story and engage us with the events unfolding.

In fifteenth-century Florentine painting, line and composition were of the highest importance. In this panel, Botticelli shows his mastery of both and proves himself one of the greatest painters of his age.

9004. The Virgin in Prayer

Sassoferrato (1609–1685)

The Virgin in Prayer

1640–1650

Oil on canvas, 73.0 x 57.7cm

The National Gallery, London.

Bequeathed by Richard Simmons, 1846

NG 200

© The National Gallery, London

Sassoferrato specialised in devotional paintings. Here, we see the Virgin Mary with her head lowered and her hands folded in prayer. The dramatic lighting, vivid use of colour, and powerful expression of emotion are characteristic of the Baroque period. They are also typical of Sassoferrato’s style, known for the intense colours, the soft modelling of the form, and the enamel-like quality.

Rome was the centre of the European art world in the seventeenth century. Many painters studied in the city and learned from past masters as an essential part of their training. Sassoferrato developed his career in Rome, where Raphael had achieved enormous fame over a century earlier. He studied Raphael’s work closely and copied them, including the painting to your left, commonly known as “The Garvagh Madonna”.

Sassoferrato admired his contemporary Guido Reni, whose painting, hung behind you, was also meant for quiet meditation. These close-up images of holy figures met the needs of the period, which emphasised personal and emotional religious experiences.

9004. The Virgin in Prayer

Sassoferrato specialised in devotional paintings. Here, we see the Virgin Mary with her head lowered and her hands folded in prayer. The dramatic lighting, vivid use of colour, and powerful expression of emotion are characteristic of the Baroque period. They are also typical of Sassoferrato’s style, known for the intense colours, the soft modelling of the form, and the enamel-like quality.

Rome was the centre of the European art world in the seventeenth century. Many painters studied in the city and learned from past masters as an essential part of their training. Sassoferrato developed his career in Rome, where Raphael had achieved enormous fame over a century earlier. He studied Raphael’s work closely and copied them, including the painting to your left, commonly known as “The Garvagh Madonna”.

Sassoferrato admired his contemporary Guido Reni, whose painting, hung behind you, was also meant for quiet meditation. These close-up images of holy figures met the needs of the period, which emphasised personal and emotional religious experiences.

9005. The Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist (“The Garvagh Madonna”)

Raphael (1483–1520)

The Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John

the Baptist (“The Garvagh Madonna”)

About 1510–1511

Oil on wood, 38.9 x 32.9cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought, 1865

NG 744

© The National Gallery, London

Raphael has long been recognised as the supreme painter of the early sixteenth century. The figures of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child in this painting form a triangle compositionally with St John the Baptist. For this painting, Raphael experimented with the poses of the mother and child in a preparatory sketch. The muted colours of the hazy background echo the pink of the Virgin’s dress and the blues of her shirt and mantle. Through the window we can see a church on the left and a larger structure to the right. These buildings are different from any of the background architecture Raphael had painted before he arrived in Rome.

This painting is representative of the harmonious, highly controlled, and classically balanced art of the High Renaissance (1490s–1527). Other great artists of the period were Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Titian. These masters enjoyed a completely new and elevated status and were admired for their “divine” powers as artists rather than mere craftsmen. Raphael probably painted this work for private devotion while he was in Rome creating a sequence of frescoes for the Vatican.

9005. The Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist (“The Garvagh Madonna”)

Raphael has long been recognised as the supreme painter of the early sixteenth century. The figures of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child in this painting form a triangle compositionally with St John the Baptist. For this painting, Raphael experimented with the poses of the mother and child in a preparatory sketch. The muted colours of the hazy background echo the pink of the Virgin’s dress and the blues of her shirt and mantle. Through the window we can see a church on the left and a larger structure to the right. These buildings are different from any of the background architecture Raphael had painted before he arrived in Rome.

This painting is representative of the harmonious, highly controlled, and classically balanced art of the High Renaissance (1490s–1527). Other great artists of the period were Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Titian. These masters enjoyed a completely new and elevated status and were admired for their “divine” powers as artists rather than mere craftsmen. Raphael probably painted this work for private devotion while he was in Rome creating a sequence of frescoes for the Vatican.

9006. The Virgin and Child Enthroned, with Four Angels

Quinten Massys (1465/6–1530)

The Virgin and Child Enthroned, with Four Angels

About 1506–1509

Oil on oak, 62.3 x 43.5cm

The National Gallery, London. Bequeathed by C. W. Dyson Perrins, 1958

NG 6282

© The National Gallery, London

Quinten Massys was a notable portraitist and religious painter in Low Countries. Looking closely at this painting we can see the deft and confident strokes and dots of yellow paint that Massys used to depict the glistening pearls and gems on the Virgin’s crown and the gold threads on the embroidered hem of her mantle. For her face, Massys first used a layer of undermodelling with white and grey. He then applied very light, pink flesh tints. The finer details, such as the angels’ fluffy hair, also show the artist’s mastery of the oil medium.

Oil paint is made by mixing a dry pigment with oil. Oils of different kinds, such as linseed, walnut, and poppy, can be used. Oil paint dries slowly and is more flexible than egg tempera, which artists enjoyed using for many centuries. In the early fifteenth century, artists in the Low Countries, where the Netherlands and Belgium are today, began to use oil paint systematically in thin, translucent glazes. This enabled them to depict the real world with incredible precision and vibrancy of colours. The development of this technique revolutionised painting in Europe; its impact was felt as far away as Venice and Rome.

9006. The Virgin and Child Enthroned, with Four Angels

Quinten Massys was a notable portraitist and religious painter in Low Countries. Looking closely at this painting we can see the deft and confident strokes and dots of yellow paint that Massys used to depict the glistening pearls and gems on the Virgin’s crown and the gold threads on the embroidered hem of her mantle. For her face, Massys first used a layer of undermodelling with white and grey. He then applied very light, pink flesh tints. The finer details, such as the angels’ fluffy hair, also show the artist’s mastery of the oil medium.

Oil paint is made by mixing a dry pigment with oil. Oils of different kinds, such as linseed, walnut, and poppy, can be used. Oil paint dries slowly and is more flexible than egg tempera, which artists enjoyed using for many centuries. In the early fifteenth century, artists in the Low Countries, where the Netherlands and Belgium are today, began to use oil paint systematically in thin, translucent glazes. This enabled them to depict the real world with incredible precision and vibrancy of colours. The development of this technique revolutionised painting in Europe; its impact was felt as far away as Venice and Rome.

9007. The Nurture of Bacchus

Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665)

The Nurture of Bacchus

About 1628

Oil on canvas, 80.9 x 97.7cm

The National Gallery, London.

Bequeathed by G. J. Cholmondeley, 1831; entered the Collection, 1836

NG 39

© The National Gallery, London

Seventeenth-century French painter Nicolas Poussin was a great master of classicism. In this painting, the muscular figures and the fabric draping over them show his fascination with ancient Greek and Roman art. The composition shows influences of classical relief sculptures, as well as inspiration from sixteenth-century Venetian paintings by Titian and Giovanni Bellini in Roman collections.

When we say “classical”, we often refer to the art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome. Poussin was inspired by the artistic styles of the Greco-Roman era. He studied every aspect of the classical past and aimed to re-create that world for his educated patrons in Rome and Paris. In turn, the works he created came to be regarded as “classical”.

In the seventeenth century, Italy became home to painters from all over the European continent, including Poussin. Although he was born in Normandy in northern France, he spent most of his career working in Rome.

9007. The Nurture of Bacchus

Seventeenth-century French painter Nicolas Poussin was a great master of classicism. In this painting, the muscular figures and the fabric draping over them show his fascination with ancient Greek and Roman art. The composition shows influences of classical relief sculptures, as well as inspiration from sixteenth-century Venetian paintings by Titian and Giovanni Bellini in Roman collections.

When we say “classical”, we often refer to the art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome. Poussin was inspired by the artistic styles of the Greco-Roman era. He studied every aspect of the classical past and aimed to re-create that world for his educated patrons in Rome and Paris. In turn, the works he created came to be regarded as “classical”.

In the seventeenth century, Italy became home to painters from all over the European continent, including Poussin. Although he was born in Normandy in northern France, he spent most of his career working in Rome.

9008. Boy Bitten by a Lizard

Caravaggio (1571–1610)

Boy Bitten by a Lizard

About 1594–1595

Oil on canvas, 66.0 x 49.5cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought with

the aid of a contribution from the J. Paul Getty Jr Endowment Fund, 1986

NG 6504

© The National Gallery, London

Born in 1571, Caravaggio is one of the most revolutionary figures in the history of art. One of the groundbreaking aspects of his art was his dedication to painting from nature. Caravaggio believed in studying nature to capture its essence faithfully. Look at the highly realistic still life of cherries and plums. There is also a glass vase holding a rose and a sprig of jasmine. Take an even closer look and you will see the reflection of a room on the glass surface.

Another unique trait of Caravaggio’s technique was his direct approach to painting human figures. He would paint them directly onto the canvas, without making numerous preliminary sketches on paper. Note the way he has accentuated the extreme expression of the boy with dramatic lighting effects and strong contrasts between light and dark.

Caravaggio painted this piece in his early period in Rome when he was around twenty-three years old. Interestingly, historical accounts tell us that this painting was sold on the open market and the artist received very little money for it. However, the image proved to be very popular, giving rise to the creation of numerous copies and derivations in the early seventeenth century. Inspired by Caravaggio’s original composition, these copies often depicted boys being bitten by crayfish, crabs, or scorpions.

9008. Boy Bitten by a Lizard

Born in 1571, Caravaggio is one of the most revolutionary figures in the history of art. One of the groundbreaking aspects of his art was his dedication to painting from nature. Caravaggio believed in studying nature to capture its essence faithfully. Look at the highly realistic still life of cherries and plums. There is also a glass vase holding a rose and a sprig of jasmine. Take an even closer look and you will see the reflection of a room on the glass surface.

Another unique trait of Caravaggio’s technique was his direct approach to painting human figures. He would paint them directly onto the canvas, without making numerous preliminary sketches on paper. Note the way he has accentuated the extreme expression of the boy with dramatic lighting effects and strong contrasts between light and dark.

Caravaggio painted this piece in his early period in Rome when he was around twenty-three years old. Interestingly, historical accounts tell us that this painting was sold on the open market and the artist received very little money for it. However, the image proved to be very popular, giving rise to the creation of numerous copies and derivations in the early seventeenth century. Inspired by Caravaggio’s original composition, these copies often depicted boys being bitten by crayfish, crabs, or scorpions.

9009. A Musical Party in a Courtyard

Pieter de Hooch (1629–after 1684)

A Musical Party in a Courtyard

1677

Oil on canvas, 83.5 x 68.5cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought 1916

NG 3047

© The National Gallery, London

A small group of people has gathered in a courtyard. In the dim foreground we can easily spot a seated woman by the pearl necklace and pearl earrings she is wearing. Note how she daintily holds a fine silver stirrer and a glass with a delicate base. These items indicate her refined taste and wealth. The carpet and the orange on the table are both expensive imported goods, showing the high status of the people in the painting.

Looking to the right, we see a cityscape in the background. It is most probably Amsterdam. Seventeenth-century Dutch artist Pieter de Hooch was known for depicting figures in courtyards. This was a subject that he explored throughout his career. In this composition, he has masterfully created spatial depth by incorporating the view of the outside world. Note where his signature and date are inscribed above the archway.

Following its independence from Spain in the seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic enjoyed a “Golden Age” of unprecedented wealth and became influential in European intellectual and artistic circles. Thanks to the successful activities of its merchants, shippers, bankers and manufacturers, a new social elite emerged. This elite class became patrons of the arts, commissioning paintings like this one to decorate their homes and demonstrate their status.

9009. A Musical Party in a Courtyard

A small group of people has gathered in a courtyard. In the dim foreground we can easily spot a seated woman by the pearl necklace and pearl earrings she is wearing. Note how she daintily holds a fine silver stirrer and a glass with a delicate base. These items indicate her refined taste and wealth. The carpet and the orange on the table are both expensive imported goods, showing the high status of the people in the painting.

Looking to the right, we see a cityscape in the background. It is most probably Amsterdam. Seventeenth-century Dutch artist Pieter de Hooch was known for depicting figures in courtyards. This was a subject that he explored throughout his career. In this composition, he has masterfully created spatial depth by incorporating the view of the outside world. Note where his signature and date are inscribed above the archway.

Following its independence from Spain in the seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic enjoyed a “Golden Age” of unprecedented wealth and became influential in European intellectual and artistic circles. Thanks to the successful activities of its merchants, shippers, bankers and manufacturers, a new social elite emerged. This elite class became patrons of the arts, commissioning paintings like this one to decorate their homes and demonstrate their status.

9010. Portrait of a Girl

Workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio

(1449–1494)

Portrait of a Girl

Probably about 1490

Tempera on wood, 44.1 x 29.2cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought, 1887

NG 1230

© The National Gallery, London

This late fifteenth-century portrait was made by an unknown artist from Domenico Ghirlandaio’s workshop, in his style. Ghirlandaio was a renowned painter whose workshop included his brothers, brother-in-law, and son. Interestingly, one of his apprentices happened to be the young Michelangelo. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, painting was considered a craft, and some artists operated workshops. These workshops had apprentices and assistants, and sometimes a chief artist would work on a painting without the master’s participation. Such paintings are called “workshop” pieces.

The Renaissance in Europe saw an important new interest in lifelike portraiture. Unlike generic depictions, these portraits celebrated the individuality of the sitter. Artists studied the unique features of their subjects from life, although they often idealised them to some extent. This approach was inspired by ancient Greece and Rome, where recognisable images of men and women appeared in sculpture and on coins.

9010. Portrait of a Girl

This late fifteenth-century portrait was made by an unknown artist from Domenico Ghirlandaio’s workshop, in his style. Ghirlandaio was a renowned painter whose workshop included his brothers, brother-in-law, and son. Interestingly, one of his apprentices happened to be the young Michelangelo. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, painting was considered a craft, and some artists operated workshops. These workshops had apprentices and assistants, and sometimes a chief artist would work on a painting without the master’s participation. Such paintings are called “workshop” pieces.

The Renaissance in Europe saw an important new interest in lifelike portraiture. Unlike generic depictions, these portraits celebrated the individuality of the sitter. Artists studied the unique features of their subjects from life, although they often idealised them to some extent. This approach was inspired by ancient Greece and Rome, where recognisable images of men and women appeared in sculpture and on coins.

9011. A Young Princess (Dorothea of Denmark?)

Jan Gossaert (Jean Gossart) (active 1508; died 1532)

A Young Princess (Dorothea of Denmark?)

About 1530–1532

Oil on oak, 38.2 x 29.1cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought 1908

NG 2211

© The National Gallery, London

This is a panel painting by Early Netherlandish artist Jan Gossaert. It was painted on high-quality oak, the most durable wood available in Northern Europe at the time. Over the years, the paint has become more transparent, allowing us to see the layers beneath. Look closely at the hands and clothing, where extensive freehand underdrawing is visible.

The oak support for this painting was prepared in a typical manner. It was first coated in a layer of animal glue, then covered with chalk, and finally, lead-white priming. This process created a smooth surface for the artist to work on. After drawing the outlines of the image, the artist would then meticulously apply oil paint.

It is interesting to note that from the fifteenth century to the mid-sixteenth century, most northern European paintings now in the collection of the National Gallery were painted on wood panels. In Germany, artists used different types of wood depending on the local trees available in the country’s highly forested regions. These range from oak, beech, and lime, to spruce, fir, pine, elm, and maple. However, most Early Netherlandish paintings, including this one, were painted on oak. The Baltic region of Europe was a major source of oak for these artworks.

9011. A Young Princess (Dorothea of Denmark?)

This is a panel painting by Early Netherlandish artist Jan Gossaert. It was painted on high-quality oak, the most durable wood available in Northern Europe at the time. Over the years, the paint has become more transparent, allowing us to see the layers beneath. Look closely at the hands and clothing, where extensive freehand underdrawing is visible.

The oak support for this painting was prepared in a typical manner. It was first coated in a layer of animal glue, then covered with chalk, and finally, lead-white priming. This process created a smooth surface for the artist to work on. After drawing the outlines of the image, the artist would then meticulously apply oil paint.

It is interesting to note that from the fifteenth century to the mid-sixteenth century, most northern European paintings now in the collection of the National Gallery were painted on wood panels. In Germany, artists used different types of wood depending on the local trees available in the country’s highly forested regions. These range from oak, beech, and lime, to spruce, fir, pine, elm, and maple. However, most Early Netherlandish paintings, including this one, were painted on oak. The Baltic region of Europe was a major source of oak for these artworks.

9012. Self Portrait at the Age of 63

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

Self Portrait at the Age of 63

1669

Oil on canvas, 86 x 70.5cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought, 1851

NG 221

© The National Gallery, London

Rembrandt is one of the most famous Dutch painters of all time. This is a thoughtful and honest self-portrait by Rembrandt in his later years. Looking closely at the painting, you can see the brushstrokes on the canvas. Rembrandt used thick layers of paint, creating a textured effect. This technique is called impasto.

To make oil paint, artists mix dry pigments with oil, grinding them together thoroughly to achieve the consistency they require. The oil and pigment used, as well as their proportions, determine the colour and texture of the paint.

In this self-portrait, you can see the impasto technique most clearly on Rembrandt’s face and fur collar. The texture adds depth and dimension to the painting, making it come alive.

Pay attention to the costume Rembrandt is wearing in this self-portrait. This kind of tight-fitting, high-collared, fur-lined jacket, known as a doublet, is seen in costumes depicted in famous paintings from the 1400s and after. Rembrandt’s choice of costume suggests that he is proudly aligning himself with renowned artists and well-established traditions of the past.

9012. Self Portrait at the Age of 63

Rembrandt is one of the most famous Dutch painters of all time. This is a thoughtful and honest self-portrait by Rembrandt in his later years. Looking closely at the painting, you can see the brushstrokes on the canvas. Rembrandt used thick layers of paint, creating a textured effect. This technique is called impasto.

To make oil paint, artists mix dry pigments with oil, grinding them together thoroughly to achieve the consistency they require. The oil and pigment used, as well as their proportions, determine the colour and texture of the paint.

In this self-portrait, you can see the impasto technique most clearly on Rembrandt’s face and fur collar. The texture adds depth and dimension to the painting, making it come alive.

Pay attention to the costume Rembrandt is wearing in this self-portrait. This kind of tight-fitting, high-collared, fur-lined jacket, known as a doublet, is seen in costumes depicted in famous paintings from the 1400s and after. Rembrandt’s choice of costume suggests that he is proudly aligning himself with renowned artists and well-established traditions of the past.

9013. Portrait of Vincenzo Morosini

Jacopo Tintoretto (about 1518–1594)

Portrait of Vincenzo Morosini

About 1575–1580

Oil on canvas, 85.3 x 52.2cm

The National Gallery, London. Presented by the Art Fund in commemoration of the Fund’s coming of age and of the National Gallery Centenary, 1924

NG 4004

© The National Gallery, London

Jacopo Tintoretto was one of the three giants of sixteenth-century Venetian painting, along with Titian and Veronese.

Look at the streaks of yellow outlining the sitter’s stole and the squiggles of crimson in his robe in this painting. Tintoretto’s brushwork is loose and visible and is often described as “painterly”. But some of his contemporaries saw his work as rough and unfinished. The Renaissance painter and biographer Giorgio Vasari, wrote in his book The Lives of Artists that Tintoretto “was a great master but never finished a painting”.

Tintoretto painted on canvas, a cloth usually made of linen or hemp. The use of canvas amplifies the already painterly quality of Tintoretto’s works of art. The drier the brush and the coarser the weave of the canvas, the stronger the visual impact of the brushwork. Technical analysis reveals that Tintoretto used a wide variety of canvases with different types of weave.

Canvas painting began to gain popularity in Italy around the year 1500, although wood panels were still widely used in Europe, especially in the north. Canvas was preferred for its affordability and ease of production in comparison with wood panels. The varying textures of canvas also offered artists more creative possibilities to experiment with.

9013. Portrait of Vincenzo Morosini

Jacopo Tintoretto was one of the three giants of sixteenth-century Venetian painting, along with Titian and Veronese.

Look at the streaks of yellow outlining the sitter’s stole and the squiggles of crimson in his robe in this painting. Tintoretto’s brushwork is loose and visible and is often described as “painterly”. But some of his contemporaries saw his work as rough and unfinished. The Renaissance painter and biographer Giorgio Vasari, wrote in his book The Lives of Artists that Tintoretto “was a great master but never finished a painting”.

Tintoretto painted on canvas, a cloth usually made of linen or hemp. The use of canvas amplifies the already painterly quality of Tintoretto’s works of art. The drier the brush and the coarser the weave of the canvas, the stronger the visual impact of the brushwork. Technical analysis reveals that Tintoretto used a wide variety of canvases with different types of weave.

Canvas painting began to gain popularity in Italy around the year 1500, although wood panels were still widely used in Europe, especially in the north. Canvas was preferred for its affordability and ease of production in comparison with wood panels. The varying textures of canvas also offered artists more creative possibilities to experiment with.

9014. A Dutch Ship and Other Small Vessels in a Strong Breeze

Willem van de Velde (1633–1707)

A Dutch Ship and Other Small Vessels in a Strong Breeze

1658

Oil on canvas, 55.0 x 70.0cm

The National Gallery, London. Salting Bequest, 1910

NG 2573

© The National Gallery, London

Look at the precisely painted boats in this painting. Note the warship with its gunports on the side and figurehead projecting from the front. The artist’s father, Willem van de Velde the Elder, was highly respected for his accurate marine drawings and pen paintings. It is evident from this painting that van de Velde the Younger inherited his father’s talent and expertise.

The van de Veldes came from a seafaring background and had themselves gone on sea expeditions. With their first-hand experience and deep understanding of ships, fleets, and naval battles, they depicted these subjects with great sensitivity. Their artistic legacy influenced generations of artists, including Turner, who famously said a van de Velde stormy seascape inspired him to become a painter.

During the seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic was a dominant maritime power. In this Golden Age of Dutch naval supremacy and mercantile influence, Dutch ships carried trade goods across the globe, to and from the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Dutch artists were fascinated by maritime scenes and painted all types of vessels in every imaginable condition at sea and along the shore.

9014. A Dutch Ship and Other Small Vessels in a Strong Breeze

Look at the precisely painted boats in this painting. Note the warship with its gunports on the side and figurehead projecting from the front. The artist’s father, Willem van de Velde the Elder, was highly respected for his accurate marine drawings and pen paintings. It is evident from this painting that van de Velde the Younger inherited his father’s talent and expertise.

The van de Veldes came from a seafaring background and had themselves gone on sea expeditions. With their first-hand experience and deep understanding of ships, fleets, and naval battles, they depicted these subjects with great sensitivity. Their artistic legacy influenced generations of artists, including Turner, who famously said a van de Velde stormy seascape inspired him to become a painter.

During the seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic was a dominant maritime power. In this Golden Age of Dutch naval supremacy and mercantile influence, Dutch ships carried trade goods across the globe, to and from the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Dutch artists were fascinated by maritime scenes and painted all types of vessels in every imaginable condition at sea and along the shore.

-600x600-1698905573.jpg)

9015. The Parting of Hero and Leander—from the Greek of Musaeus

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

The Parting of Hero and Leander—from the Greek

of Musaeus

Before 1837

Oil on canvas, 146 x 236cm

The National Gallery, London. Turner Bequest, 1856

NG 521

© The National Gallery, London

On view in this section are two monumental paintings by Joseph Mallord William Turner and John Constable. First, we have Turner’s The Painting of Hero and Leander which is among the finest examples of his powerful scenes of literary allusion. Take a moment to appreciate the vibrant energy and dramatic lighting of the skies and sea in the painting. Notice the contrast between the turbulent waves of sea nymphs on the right and the orderly receding staircase and classical city on the left.

In contrast, Constable’s Stratford Mill presents an entirely different representation of nature—a calm, natural scene of his native Suffolk, in the east of England. The painting carries a sense of nostalgia.

Both Turner and Constable are associated with Romanticism, an art movement characterised by individuality, emotional intensity, and an affinity with the natural world. These two paintings exemplify the multifaceted nature of Romanticism, which encompasses a vast range of artistic styles. Constable once described painting as “another word for feeling”. Charles Baudelaire, a French poet and art critic, shared a similar view, saying: “Romanticism is precisely situated neither in choice of subject nor in exact truth, but in a way of feeling.”

9015. The Parting of Hero and Leander—from the Greek of Musaeus

On view in this section are two monumental paintings by Joseph Mallord William Turner and John Constable. First, we have Turner’s The Painting of Hero and Leander which is among the finest examples of his powerful scenes of literary allusion. Take a moment to appreciate the vibrant energy and dramatic lighting of the skies and sea in the painting. Notice the contrast between the turbulent waves of sea nymphs on the right and the orderly receding staircase and classical city on the left.

In contrast, Constable’s Stratford Mill presents an entirely different representation of nature—a calm, natural scene of his native Suffolk, in the east of England. The painting carries a sense of nostalgia.

Both Turner and Constable are associated with Romanticism, an art movement characterised by individuality, emotional intensity, and an affinity with the natural world. These two paintings exemplify the multifaceted nature of Romanticism, which encompasses a vast range of artistic styles. Constable once described painting as “another word for feeling”. Charles Baudelaire, a French poet and art critic, shared a similar view, saying: “Romanticism is precisely situated neither in choice of subject nor in exact truth, but in a way of feeling.”

9016. Venice: Entrance to the Cannaregio

Canaletto (1697–1768)

Venice: Entrance to the Cannaregio

Probably 1734–1742

Oil on canvas, 48 x 80.2cm

The National Gallery, London. Bequeathed by John Henderson, 1879

NG 1058

© The National Gallery, London

Canaletto appears to have favoured beauty over accuracy, as this painting indicates. Here, he presents Venice through his eyes, creating an illusion that tricks us into believing we are seeing the actual city. However, upon closer inspection, we notice some artistic liberties have been taken. The palace at the right edge is more pronounced and at a sharper angle than in real life. The bell tower to the left appears slenderer, and the bridge in the centre is larger than life, deliberately brought closer to us for pictorial effect. The whole canal is more open than in reality.

By the mid-1730s, Canaletto was the most sought-after artist in Venice. He created multiple versions of similar compositions to meet the growing demand for his work. It is important to note that none of his paintings were made in situ. Many eighteenth-century landscape painters used a tool called the camera obscura in the creative process. Canaletto probably used this early predecessor of the camera to capture accurate views of the city. Attesting to this is the protective cover of such a device housed in the Museo Correr in Venice and inscribed with “A. CANAL”, an abbreviation of his name.

9016. Venice: Entrance to the Cannaregio

Canaletto appears to have favoured beauty over accuracy, as this painting indicates. Here, he presents Venice through his eyes, creating an illusion that tricks us into believing we are seeing the actual city. However, upon closer inspection, we notice some artistic liberties have been taken. The palace at the right edge is more pronounced and at a sharper angle than in real life. The bell tower to the left appears slenderer, and the bridge in the centre is larger than life, deliberately brought closer to us for pictorial effect. The whole canal is more open than in reality.

By the mid-1730s, Canaletto was the most sought-after artist in Venice. He created multiple versions of similar compositions to meet the growing demand for his work. It is important to note that none of his paintings were made in situ. Many eighteenth-century landscape painters used a tool called the camera obscura in the creative process. Canaletto probably used this early predecessor of the camera to capture accurate views of the city. Attesting to this is the protective cover of such a device housed in the Museo Correr in Venice and inscribed with “A. CANAL”, an abbreviation of his name.

9017. Seaport with the Embarkation of Saint Ursula

Claude (1604 or 1605–1682)

Seaport with the Embarkation of Saint Ursula

1641

Oil on canvas, 112.9 x 149.0cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought, 1824

NG 30

© The National Gallery, London

Seventeenth-century French painter Claude Lorrain, also known as Claude Gellée, or simply, Claude had a tremendous influence on landscape artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including Turner and Constable. Claude’s landscapes are often called “classical” because their balanced compositions evoke a peaceful and idealised mood reminiscent of the classical past. They became a standard against which real scenery was judged. In fact, some English landowners were so inspired by Claude’s paintings that they redeveloped the gardens of their country houses to resemble his works of art.

This painting is part of a pair or pendant. Its counterpart, Landscape with Saint George and the Dragon, is now housed in the Wadsworth Atheneum, Connecticut, USA. Pendant paintings are meant to be hung side by side. They were a favourite format with Claude and he produced many of his works in this manner, sometimes two or more years apart. The pairs may complement each other because of either their commonalities or contrasts. In this example, a port and harbour scene is paired with a classical landscape with distant mountains. This pairing encourages viewers to reflect more deeply on the meaning of each painting. In this section, we also have Salvator Rosa’s painting, Landscape with Mercury and the Dishonest Woodman, whose pendant is The Finding of Moses, now located in the Detroit Institute of Arts.

9017. Seaport with the Embarkation of Saint Ursula

Seventeenth-century French painter Claude Lorrain, also known as Claude Gellée, or simply, Claude had a tremendous influence on landscape artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including Turner and Constable. Claude’s landscapes are often called “classical” because their balanced compositions evoke a peaceful and idealised mood reminiscent of the classical past. They became a standard against which real scenery was judged. In fact, some English landowners were so inspired by Claude’s paintings that they redeveloped the gardens of their country houses to resemble his works of art.

This painting is part of a pair or pendant. Its counterpart, Landscape with Saint George and the Dragon, is now housed in the Wadsworth Atheneum, Connecticut, USA. Pendant paintings are meant to be hung side by side. They were a favourite format with Claude and he produced many of his works in this manner, sometimes two or more years apart. The pairs may complement each other because of either their commonalities or contrasts. In this example, a port and harbour scene is paired with a classical landscape with distant mountains. This pairing encourages viewers to reflect more deeply on the meaning of each painting. In this section, we also have Salvator Rosa’s painting, Landscape with Mercury and the Dishonest Woodman, whose pendant is The Finding of Moses, now located in the Detroit Institute of Arts.

9018. Irises

Claude Monet (1840–1926)

Irises

About 1914–1917

Oil on canvas, 200.7 x 149.9cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought, 1967

NG 6383

© The National Gallery, London

Impressionist painter Claude Monet once advised a young painter: “When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field, or whatever. Merely think here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact colour and shape, until it gives your own naïve impression of the scene before you.”

The tradition of painting outdoors, also known as open-air, or in French, plein-air, painting, can be traced back to the late eighteenth century in Rome. Young artists went out to the countryside to capture the essence of nature through direct observation. They painted oil sketches outdoors as exercises and resources for reference. These sketches were not intended for public display. Monet and his fellow Impressionists broke away from this tradition by publicly displaying their open-air paintings conveying the sensations of nature.

Irises, the painting we are discussing, had not, however, been meant for sale or exhibition. It was part of Monet’s studies for a huge installation, known as the Grand Decorations, featuring the water garden at his home in Giverny.

9018. Irises

Impressionist painter Claude Monet once advised a young painter: “When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field, or whatever. Merely think here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact colour and shape, until it gives your own naïve impression of the scene before you.”

The tradition of painting outdoors, also known as open-air, or in French, plein-air, painting, can be traced back to the late eighteenth century in Rome. Young artists went out to the countryside to capture the essence of nature through direct observation. They painted oil sketches outdoors as exercises and resources for reference. These sketches were not intended for public display. Monet and his fellow Impressionists broke away from this tradition by publicly displaying their open-air paintings conveying the sensations of nature.

Irises, the painting we are discussing, had not, however, been meant for sale or exhibition. It was part of Monet’s studies for a huge installation, known as the Grand Decorations, featuring the water garden at his home in Giverny.

9019. Bowl of Fruit and Tankard before a Window

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

Bowl of Fruit and Tankard before a Window

Probably 1890

Oil on canvas, 50.8 x 61.6cm

Bequeathed by Simon Sainsbury, 2006

NG 6609

© The National Gallery, London

Nineteenth-century French painter Paul Gauguin uses colour to construct space and form in this painting. Every part of the composition has equal importance. He depicts the white cloth with pale greens, blues, pinks, and greys and creates the fruits with solid strokes of contrasting colours. Notice the background of rooftops composed of diagonal, horizontal, and vertical lines, and planes of colour, recalling the rooftops in Paul Cézanne’s landscapes. This painting is, in fact, modelled upon Cézanne’s Still Life with Fruit Dish.

Both Gauguin and Cézanne are among the artists the English art critic Roger Fry identified as Post-Impressionists. Fry coined the term Post-Impressionism in 1910 to make sense of the paintings that came after Impressionism, which were diverse in subject matter and technique. Cézanne exhibited in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 and Gauguin in the eighth and final one in 1886. Both artists were deeply impressed by the radical breakthroughs of Impressionism, but sought to move beyond visual effects and explore the symbolic or expressive possibilities of art, using colour in distinctive ways to create form.

9019. Bowl of Fruit and Tankard before a Window

Nineteenth-century French painter Paul Gauguin uses colour to construct space and form in this painting. Every part of the composition has equal importance. He depicts the white cloth with pale greens, blues, pinks, and greys and creates the fruits with solid strokes of contrasting colours. Notice the background of rooftops composed of diagonal, horizontal, and vertical lines, and planes of colour, recalling the rooftops in Paul Cézanne’s landscapes. This painting is, in fact, modelled upon Cézanne’s Still Life with Fruit Dish.

Both Gauguin and Cézanne are among the artists the English art critic Roger Fry identified as Post-Impressionists. Fry coined the term Post-Impressionism in 1910 to make sense of the paintings that came after Impressionism, which were diverse in subject matter and technique. Cézanne exhibited in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 and Gauguin in the eighth and final one in 1886. Both artists were deeply impressed by the radical breakthroughs of Impressionism, but sought to move beyond visual effects and explore the symbolic or expressive possibilities of art, using colour in distinctive ways to create form.

9020. Long Grass with Butterflies

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

Long Grass with Butterflies

1890

Oil on canvas, 64.5 x 80.7cm

The National Gallery, London. Bought, Courtauld Fund, 1926

NG 4169

© The National Gallery, London

Vincent van Gogh is possibly the world’s most popular Post-Impressionist painter.

He was passionate about painting outdoors. In an early letter to his brother Theo, the artist advised: “Always continue walking a lot and loving nature, for that’s the real way to learn to understand art better and better. Painters understand nature and love it and teach us to see.”

In this painting, van Gogh’s energetic paint strokes are so thick that they stand out in relief, lending it a tactile, almost sculptural quality. This technique of laying on thick strokes of paint with a brush or palette knife is called impasto. The heavy surface sometimes trapped grains of sand, pebbles, or bits of plants, and even the footprints of insects.

Van Gogh described his method in a letter to his friend Emile Bernard: “While always working directly on the spot, I try to capture the essence in the drawing—then I fill the spaces demarcated by the outlines.” Later in his life, he wrote: “It isn’t the language of painters one ought to listen to but the language of nature.”

9020. Long Grass with Butterflies

Vincent van Gogh is possibly the world’s most popular Post-Impressionist painter.

He was passionate about painting outdoors. In an early letter to his brother Theo, the artist advised: “Always continue walking a lot and loving nature, for that’s the real way to learn to understand art better and better. Painters understand nature and love it and teach us to see.”

In this painting, van Gogh’s energetic paint strokes are so thick that they stand out in relief, lending it a tactile, almost sculptural quality. This technique of laying on thick strokes of paint with a brush or palette knife is called impasto. The heavy surface sometimes trapped grains of sand, pebbles, or bits of plants, and even the footprints of insects.

Van Gogh described his method in a letter to his friend Emile Bernard: “While always working directly on the spot, I try to capture the essence in the drawing—then I fill the spaces demarcated by the outlines.” Later in his life, he wrote: “It isn’t the language of painters one ought to listen to but the language of nature.”

-600x600-1698905573.jpg)