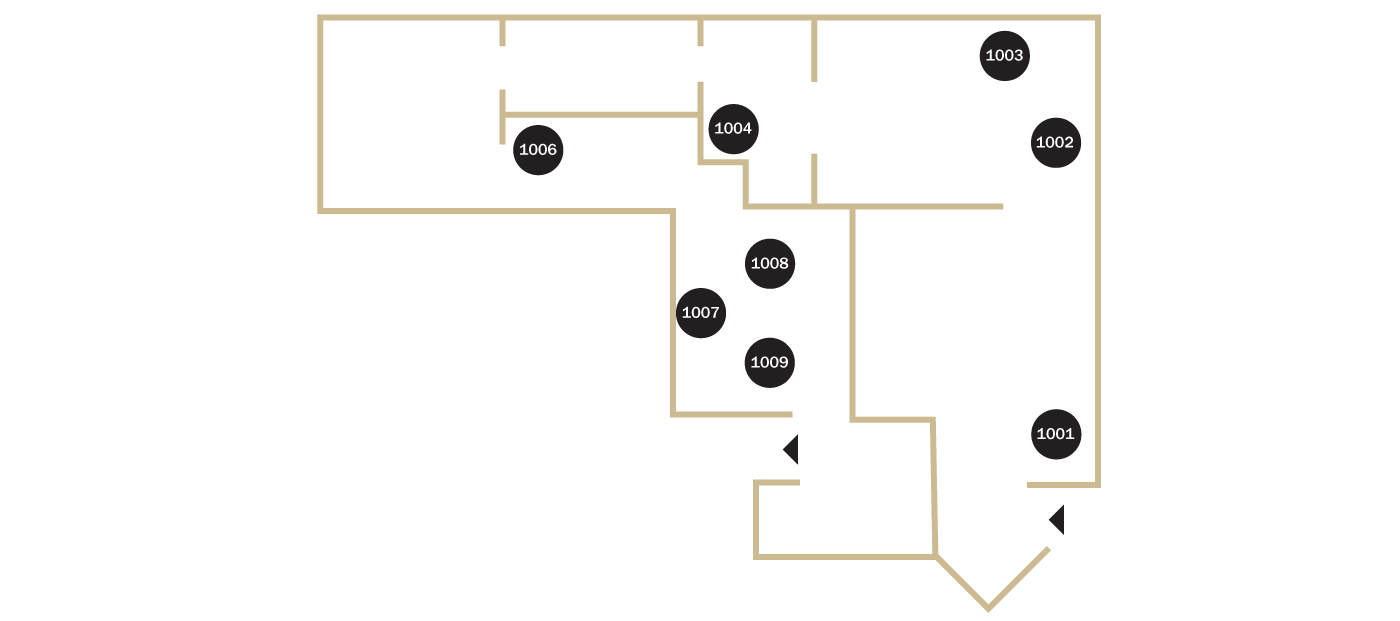

1001. The “Gold” Tiles

Interior of Hall of Supreme Harmony

© The Palace Museum

The “Gold” Tiles

Narrator: “A “gold” floor tile craftsman in Suzhou was chatting with his apprentice while working.”(The sound of cutting and grinding tiles.)

Apprentice: “Master, I heard that tiles produced in Suzhou are used in imperial palaces, and that they are called ‘gold floor tiles’. Is that true?”

Master: “Look at you! You’ve learned something! You can see our tiles are dark in colour. (sound of the master knocking twice on a piece of tile). The sound is clear and loud (the master knocks twice more), like knocking on metal, which is why people call them ‘gold’ floor tiles.”

Apprentice: “The biggest tile we can make is 69 square centimetres. When do you think we will make an even bigger gold tile?”

Master: “Haha! Foolish boy! The bigger the tile, the more difficult it is to fire. In the past, firing a piece of 63 square centimetres was remarkable. It was not until the reign of the Qianlong Emperor that we discovered how to manufacture tiles of 69 square centimetres, which were the best we could offer to the throne hall. The boatmen who shipped them to Beijing said the shiny floor made the hall all the more magnificent. That’s how amazing our craft is.”

Apprentice: “Heh, that’s a lot of money, right?”

Master: “Kid, let me tell you something. While the 69 square centimetres tiles are just 20% larger than those in the past, they are so difficult to produce that they are 80% more expensive. Empress Dowager Cixi required larger gold tiles measuring around 76 square centimetres for the Hall of Eminent Favour at her Mausoleum. Unfortunately, her wish could not be fulfilled, because craftsmen were limited by the technology of the time.”

Narrator: “The fact that the gold tiles were inscribed and stamped with their year and place of production, and the names of the supervisor and craftsmen who worked on them, demonstrates the rigorous quality control employed by the Qing court—as well as the pride and glory of the craftsmen.”

© The Palace Museum

1001. The “Gold” Tiles

The “Gold” Tiles

Narrator: “A “gold” floor tile craftsman in Suzhou was chatting with his apprentice while working.”(The sound of cutting and grinding tiles.)

Apprentice: “Master, I heard that tiles produced in Suzhou are used in imperial palaces, and that they are called ‘gold floor tiles’. Is that true?”

Master: “Look at you! You’ve learned something! You can see our tiles are dark in colour. (sound of the master knocking twice on a piece of tile). The sound is clear and loud (the master knocks twice more), like knocking on metal, which is why people call them ‘gold’ floor tiles.”

Apprentice: “The biggest tile we can make is 69 square centimetres. When do you think we will make an even bigger gold tile?”

Master: “Haha! Foolish boy! The bigger the tile, the more difficult it is to fire. In the past, firing a piece of 63 square centimetres was remarkable. It was not until the reign of the Qianlong Emperor that we discovered how to manufacture tiles of 69 square centimetres, which were the best we could offer to the throne hall. The boatmen who shipped them to Beijing said the shiny floor made the hall all the more magnificent. That’s how amazing our craft is.”

Apprentice: “Heh, that’s a lot of money, right?”

Master: “Kid, let me tell you something. While the 69 square centimetres tiles are just 20% larger than those in the past, they are so difficult to produce that they are 80% more expensive. Empress Dowager Cixi required larger gold tiles measuring around 76 square centimetres for the Hall of Eminent Favour at her Mausoleum. Unfortunately, her wish could not be fulfilled, because craftsmen were limited by the technology of the time.”

Narrator: “The fact that the gold tiles were inscribed and stamped with their year and place of production, and the names of the supervisor and craftsmen who worked on them, demonstrates the rigorous quality control employed by the Qing court—as well as the pride and glory of the craftsmen.”

© The Palace Museum

1002. The Kangxi Emperor’s Peerless Archery Skills

Bow of the Kangxi Emperor

© The Palace Museum

The Kangxi Emperor’s Peerless Archery Skills

Narrator: “The bow here belonged to the Kangxi Emperor. He claimed to be able to draw a bow which required about 90 kilograms of drawing strength, and that he could launch 13 arrows in quick succession. It demonstrates his extraordinary strength.”

Narrator: “In the spring of 1696, the Kangxi Emperor enjoyed an archery session with princes, Mongolian nobles, and imperial guards in the northwest of Hebei province.”

Mongolian nobles: “What marvellous archery skills! Your Majesty hit the target five times in a row! All hail the emperor, for his unparalleled martial feat!” (Applause)

Mongolian nobility: “May I try your bow, Your Majesty?”

“Ha…ha…” (Sound of the nobility drawing the bow with all his strength.)

Mongolian noble: “I made a show of myself. I really can’t draw the bow.”

Ministers: “All hail the emperor!”

Narrator: “In 1699, the emperor led the princes in another archery session at a range in Hangzhou.”

(Sounds of archery)

The Kangxi Emperor laughed proudly: “Hahaha!”

The Kangxi Emperor: “Prepare my horse. I want to shoot from horseback!”

(The clatter of a horse’s hooves.)

(Suddenly, the horse neighed.)

(The clatter of a horse’s hooves.)

Minister: “Look! The horse veered to the left. And now the emperor is shooting with his left hand!”

(The sound of archery.)

The clatter of a horse’s hooves. The neighing stops.

The audience: “The horse strayed, but the emperor still hit the target. All hail the emperor, for his unparalleled martial feat!”

© The Palace Museum

1002. The Kangxi Emperor’s Peerless Archery Skills

The Kangxi Emperor’s Peerless Archery Skills

Narrator: “The bow here belonged to the Kangxi Emperor. He claimed to be able to draw a bow which required about 90 kilograms of drawing strength, and that he could launch 13 arrows in quick succession. It demonstrates his extraordinary strength.”

Narrator: “In the spring of 1696, the Kangxi Emperor enjoyed an archery session with princes, Mongolian nobles, and imperial guards in the northwest of Hebei province.”

Mongolian nobles: “What marvellous archery skills! Your Majesty hit the target five times in a row! All hail the emperor, for his unparalleled martial feat!” (Applause)

Mongolian nobility: “May I try your bow, Your Majesty?”

“Ha…ha…” (Sound of the nobility drawing the bow with all his strength.)

Mongolian noble: “I made a show of myself. I really can’t draw the bow.”

Ministers: “All hail the emperor!”

Narrator: “In 1699, the emperor led the princes in another archery session at a range in Hangzhou.”

(Sounds of archery)

The Kangxi Emperor laughed proudly: “Hahaha!”

The Kangxi Emperor: “Prepare my horse. I want to shoot from horseback!”

(The clatter of a horse’s hooves.)

(Suddenly, the horse neighed.)

(The clatter of a horse’s hooves.)

Minister: “Look! The horse veered to the left. And now the emperor is shooting with his left hand!”

(The sound of archery.)

The clatter of a horse’s hooves. The neighing stops.

The audience: “The horse strayed, but the emperor still hit the target. All hail the emperor, for his unparalleled martial feat!”

© The Palace Museum

1003. A Red Wedding

The Grand Imperial Wedding of the Guangxu Emperor

© The Palace Museum

A Red Wedding

Narrator: “On January 16th 1889, while the court was preparing for the imperial wedding of the Guangxu emperor, a fire broke out.”

People [shouting]: “Fire! Help! Put out the fire!”

(The sound of wooden buckets colliding, fires blazing, people shouting, and rapid footsteps)

Palace maid [crying out]: “Help! The Gate of Supreme Harmony is on fire!”

Fire-fighters [yelling]: “My lord! The storerooms… Come! Save the storerooms!”

Officer: “There’s a fire in the palace. Hurry up! We must go and help them!”

(Sounds of firefighting, which gradually fade out)

Narrator: “Two days after the fire, the Guangxu Emperor issued an edict.”

The Guangxu Emperor (age 18): “Staff from the Firearms Divisions and Office of the Gendarmerie will be rewarded with two taels of silver each for fighting the blaze. The fifteen voluntary fire brigades will be rewarded with a total of ten thousand taels. But all secretaries and guardsmen on duty that day shall be interrogated by the Ministry of Justice, and the Ministry of War should propose a penalty for the Commander-General of the Vanguard Brigade on duty that night .”

Officers: “Yes, Your Majesty.”

Narrator: “The album leaf here depicts the Guangxu Emperor’s grand wedding, scheduled for a month after the fire. The chaos caused by the fire has been completely removed from the scene.”

© The Palace Museum

1003. A Red Wedding

A Red Wedding

Narrator: “On January 16th 1889, while the court was preparing for the imperial wedding of the Guangxu emperor, a fire broke out.”

People [shouting]: “Fire! Help! Put out the fire!”

(The sound of wooden buckets colliding, fires blazing, people shouting, and rapid footsteps)

Palace maid [crying out]: “Help! The Gate of Supreme Harmony is on fire!”

Fire-fighters [yelling]: “My lord! The storerooms… Come! Save the storerooms!”

Officer: “There’s a fire in the palace. Hurry up! We must go and help them!”

(Sounds of firefighting, which gradually fade out)

Narrator: “Two days after the fire, the Guangxu Emperor issued an edict.”

The Guangxu Emperor (age 18): “Staff from the Firearms Divisions and Office of the Gendarmerie will be rewarded with two taels of silver each for fighting the blaze. The fifteen voluntary fire brigades will be rewarded with a total of ten thousand taels. But all secretaries and guardsmen on duty that day shall be interrogated by the Ministry of Justice, and the Ministry of War should propose a penalty for the Commander-General of the Vanguard Brigade on duty that night .”

Officers: “Yes, Your Majesty.”

Narrator: “The album leaf here depicts the Guangxu Emperor’s grand wedding, scheduled for a month after the fire. The chaos caused by the fire has been completely removed from the scene.”

© The Palace Museum

1004. Master Craftsmen from Tibet

Stupa

© The Palace Museum

Master Craftsmen from Tibet

Narrator: “Winter, 1744.”

(A strong wind, with a lone bird calling out in the distance).

Qianlong Emperor (age 34): “It has been a century since we established our rule, yet the production of Buddhist sculptural works at the court still has not improved. Deliver my order to the Court of Colonial Affairs. Tell them to search for six outstanding craftsmen from Tibet. These craftsmen shall build the first large-scale golden stupa of the Qing dynasty.”

Officers: “Yes, Your Majesty.”

Narrator: “Two months later. Springtime.” (Birdsong)

Minister of the Imperial Workshops: “Your Highness, I have presented the structural design of the golden stupa to the emperor. His Majesty was satisfied and ordered us to proceed with designing the decorations.”

Prince: “Well done. His Majesty has entrusted me with managing the Imperial Workshops. We must deliver on this important task. Keep up the good work!”

Minister: “Yes, Your Highness.”

Narrator: “In autumn.” (Howling wind)

Prince: “Your Majesty, six craftsmen from Tibet have arrived at the capital. They should be able to start working soon. They claim that they are proficient in working with precious stones and casting gilded bronze. If provided with paper mock-ups, they are capable of accomplishing any task.”

The Qianlong Emperor: “Very good. Tell them to participate in the design of the decorative elements of the stupa and start construction. Since the stupa is to be placed in the Palace of Double Brilliance, where I lived before ascending the throne, all the materials must be perfect and the craftsmanship flawless.”

Prince: “Yes, Your Majesty.”

Narrator: “Two years later, in 1746, the magnificent golden stupa was finally completed. It has since stood in the Palace of Double Brilliance, witnessing centuries of the history in the Forbidden City.”

© The Palace Museum

1004. Master Craftsmen from Tibet

Master Craftsmen from Tibet

Narrator: “Winter, 1744.”

(A strong wind, with a lone bird calling out in the distance).

Qianlong Emperor (age 34): “It has been a century since we established our rule, yet the production of Buddhist sculptural works at the court still has not improved. Deliver my order to the Court of Colonial Affairs. Tell them to search for six outstanding craftsmen from Tibet. These craftsmen shall build the first large-scale golden stupa of the Qing dynasty.”

Officers: “Yes, Your Majesty.”

Narrator: “Two months later. Springtime.” (Birdsong)

Minister of the Imperial Workshops: “Your Highness, I have presented the structural design of the golden stupa to the emperor. His Majesty was satisfied and ordered us to proceed with designing the decorations.”

Prince: “Well done. His Majesty has entrusted me with managing the Imperial Workshops. We must deliver on this important task. Keep up the good work!”

Minister: “Yes, Your Highness.”

Narrator: “In autumn.” (Howling wind)

Prince: “Your Majesty, six craftsmen from Tibet have arrived at the capital. They should be able to start working soon. They claim that they are proficient in working with precious stones and casting gilded bronze. If provided with paper mock-ups, they are capable of accomplishing any task.”

The Qianlong Emperor: “Very good. Tell them to participate in the design of the decorative elements of the stupa and start construction. Since the stupa is to be placed in the Palace of Double Brilliance, where I lived before ascending the throne, all the materials must be perfect and the craftsmanship flawless.”

Prince: “Yes, Your Majesty.”

Narrator: “Two years later, in 1746, the magnificent golden stupa was finally completed. It has since stood in the Palace of Double Brilliance, witnessing centuries of the history in the Forbidden City.”

© The Palace Museum

1006. The Dark Story under the Starry Sky: Sons of the Kangxi Emperor

Water container in the shape of a heavenly bird

© The Palace Museum

The Dark Story under the Starry Sky: Sons of the Kangxi Emperor

Narrator: “In 1696, the Kangxi Emperor, who had a strong interest in Western science and technology, established an imperial glasshouse next to the Church of the Saviour in Beijing.”

Yinzhi (age 24): “As the eldest prince, I, Yinzhi, once accompanied Father on a campaign against the Dzungar Khanate. I was also granted the honourable title Prince Zhi. However, Yinreng is still the most beloved son of our father and has been named crown prince, just because he was born of the empress. It is not fair!”

Confidant: “I recently heard that the crown prince has become more and more arrogant and has disappointed the emperor. Your Highness should take this opportunity and find a way to impress the emperor.”

Yinzhi: “Father is fascinated by aventurine glass, which sparkles like stars in the night sky. But it is difficult to produce. Find me some Western craftsmen now. I must find a way to make it.”

Narrator: “Ten years passed and aventurine glass had still not been successfully produced. In 1708, Yinzhi accused his brother of various malicious activities and of having bad intentions. The furious Kangxi Emperor finally stripped Yinreng of his title as the crown prince.”

Yinzhi (a tone indicating a murderous action): “Father, Yinreng’s behaviour is vile and disrespectful. If you wish to be rid of him, someone could…take care of it.”

The Kangxi Emperor (age 52) [furious]: “Yinzhi!! How can you be so cruel to your brother!? It is unacceptable. Deliver my order: forbid Yinzhi from leaving his home, and strip him of his title!”

Narrator: “The emperor had Yinzhi confined at the age of 36 until his death at the age of 62.”

Narrator: “The Yongzheng Emperor, who emerged victorious from the succession struggle, also failed to produce aventurine glass. It was not until 1741 that the Qianlong Emperor’s court discovered the key to making it successfully. Finally, the sparkle of aventurine glass emerged—against the backdrop of a dark tale of fraternal rivalry.”

© The Palace Museum

1006. The Dark Story under the Starry Sky: Sons of the Kangxi Emperor

The Dark Story under the Starry Sky: Sons of the Kangxi Emperor

Narrator: “In 1696, the Kangxi Emperor, who had a strong interest in Western science and technology, established an imperial glasshouse next to the Church of the Saviour in Beijing.”

Yinzhi (age 24): “As the eldest prince, I, Yinzhi, once accompanied Father on a campaign against the Dzungar Khanate. I was also granted the honourable title Prince Zhi. However, Yinreng is still the most beloved son of our father and has been named crown prince, just because he was born of the empress. It is not fair!”

Confidant: “I recently heard that the crown prince has become more and more arrogant and has disappointed the emperor. Your Highness should take this opportunity and find a way to impress the emperor.”

Yinzhi: “Father is fascinated by aventurine glass, which sparkles like stars in the night sky. But it is difficult to produce. Find me some Western craftsmen now. I must find a way to make it.”

Narrator: “Ten years passed and aventurine glass had still not been successfully produced. In 1708, Yinzhi accused his brother of various malicious activities and of having bad intentions. The furious Kangxi Emperor finally stripped Yinreng of his title as the crown prince.”

Yinzhi (a tone indicating a murderous action): “Father, Yinreng’s behaviour is vile and disrespectful. If you wish to be rid of him, someone could…take care of it.”

The Kangxi Emperor (age 52) [furious]: “Yinzhi!! How can you be so cruel to your brother!? It is unacceptable. Deliver my order: forbid Yinzhi from leaving his home, and strip him of his title!”

Narrator: “The emperor had Yinzhi confined at the age of 36 until his death at the age of 62.”

Narrator: “The Yongzheng Emperor, who emerged victorious from the succession struggle, also failed to produce aventurine glass. It was not until 1741 that the Qianlong Emperor’s court discovered the key to making it successfully. Finally, the sparkle of aventurine glass emerged—against the backdrop of a dark tale of fraternal rivalry.”

© The Palace Museum

1007. Gift From Ryukyu

Box with dragons chasing a pearl

Ryukyu Kingdom, 18th century

Lacquer, mother-of-pearl

© The Palace Museum

Gift From Ryukyu

Sailor: “Captain, after sailing east from Fuzhou, we’ve arrived at Naha in the Kingdom of Ryukyu. We sold silk, textiles, and medicine, and bought minerals such as sulphur, copper, and tin. We can finally set sail for home.”

Captain: “It’s not all about business, you know. Do you know about the history of Ryukyu?”

Sailor: “In 1429, Chūzan united the three principalities and moved the capital to Shuri. The Ming monarchy sent envoys to confer the title of King on Hashi, Chūzan’s ruler, and bestowed on him the surname of Shō. From the late 14th to early 15th century, 36 families were sent from Fujian to the Ryukyu Kingdom to help with shipbuilding and other maritime affairs. And when a new king ascends the throne, Chinese envoys travel here to confer the proper title upon him with due ceremony. Ryukyu’s ruling class greatly admires Chinese culture and often sends students to the Directorate of Education in Beijing.”

Captain: “Huh. I didn’t expect you to know so much about the place.”

Sailor: “I’ve seen Ryukyuan lacquerware on our ship. The black lacquer inlaid with iridescent mother-of-pearl looks gorgeous. I’ve heard that the Ryukyuans presented this type of lacquer as tribute to the Qing emperor.

Captain: “Haha. Actually, this lacquer decoration technique was brought here from China. Ryukyu is rich in lacquer trees and the shells from which iridescent mother-of-pearl that decorate lacquerwares is obtained. After learning the technique from China, skilled craftsmen started to create beautiful lacquerwares for local royalty. They were also sent as tribute to China. The opening of the Sino-Ryukyu maritime trade forged ties between the two nations, leading to meaningful art exchanges over many years.”

Sailor: “That’s interesting. I should take a closer look at this lacquerware!”

© The Palace Museum

1007. Gift From Ryukyu

Gift From Ryukyu

Sailor: “Captain, after sailing east from Fuzhou, we’ve arrived at Naha in the Kingdom of Ryukyu. We sold silk, textiles, and medicine, and bought minerals such as sulphur, copper, and tin. We can finally set sail for home.”

Captain: “It’s not all about business, you know. Do you know about the history of Ryukyu?”

Sailor: “In 1429, Chūzan united the three principalities and moved the capital to Shuri. The Ming monarchy sent envoys to confer the title of King on Hashi, Chūzan’s ruler, and bestowed on him the surname of Shō. From the late 14th to early 15th century, 36 families were sent from Fujian to the Ryukyu Kingdom to help with shipbuilding and other maritime affairs. And when a new king ascends the throne, Chinese envoys travel here to confer the proper title upon him with due ceremony. Ryukyu’s ruling class greatly admires Chinese culture and often sends students to the Directorate of Education in Beijing.”

Captain: “Huh. I didn’t expect you to know so much about the place.”

Sailor: “I’ve seen Ryukyuan lacquerware on our ship. The black lacquer inlaid with iridescent mother-of-pearl looks gorgeous. I’ve heard that the Ryukyuans presented this type of lacquer as tribute to the Qing emperor.

Captain: “Haha. Actually, this lacquer decoration technique was brought here from China. Ryukyu is rich in lacquer trees and the shells from which iridescent mother-of-pearl that decorate lacquerwares is obtained. After learning the technique from China, skilled craftsmen started to create beautiful lacquerwares for local royalty. They were also sent as tribute to China. The opening of the Sino-Ryukyu maritime trade forged ties between the two nations, leading to meaningful art exchanges over many years.”

Sailor: “That’s interesting. I should take a closer look at this lacquerware!”

© The Palace Museum

1008. Languages and Foreign Diplomacy

Languages and Foreign Diplomacy

Qianlong Emperor (age 71): “My son Yongyan, look closely at this jade ewer.”

Yongyan (age 21): “This gorgeous jade ewer is inlaid with gold and precious stones. I heard it came from Hindustan, where people believe in Islam. After Father conquered Xinjiang, jades from the region were brought to the Forbidden City through tributes and gift presentations. And you love Hindustan jades.”

The Qianlong Emperor: “Yongyan, you must understand that it is necessary to study neighbouring regions in order to conduct successful diplomacy.”

The Qianlong Emperor: “As Manchus, we must be fluent in Manchu. But we also need to learn other languages to help with our diplomatic work.”

Yongyan: “I know that Father began to learn Chinese at 6 years old. At the age of 33, you started learning Mongolian.”

The Qianlong Emperor: “You’re never too old to learn. I conquered Xinjiang and started learning Uyghur at the age of 50. Although I only began to learn Mongolian and Uyghur as an adult, I have become fluent in both. At the age of 66, after conquering Jinchuan in southwestern China, I started learning the local dialect.”

Yongyan: “I remember on your 70th birthday, to welcome the Panchen Lama, you started learning the Tangut language.”

The Qianlong Emperor: “I am no master of the local dialect of Jinchuan or the Tangut language, but every year, when I have an audience with Mongolian, Uyghur, and Jinchuan delegates, I use their languages to greet them. There is no need for interpreters. To develop and maintain good relationships with neighbouring regions, we must never stop learning.”

Yongyan: “I will keep this lesson in mind.”

© The Palace Museum

1008. Languages and Foreign Diplomacy

Languages and Foreign Diplomacy

Qianlong Emperor (age 71): “My son Yongyan, look closely at this jade ewer.”

Yongyan (age 21): “This gorgeous jade ewer is inlaid with gold and precious stones. I heard it came from Hindustan, where people believe in Islam. After Father conquered Xinjiang, jades from the region were brought to the Forbidden City through tributes and gift presentations. And you love Hindustan jades.”

The Qianlong Emperor: “Yongyan, you must understand that it is necessary to study neighbouring regions in order to conduct successful diplomacy.”

The Qianlong Emperor: “As Manchus, we must be fluent in Manchu. But we also need to learn other languages to help with our diplomatic work.”

Yongyan: “I know that Father began to learn Chinese at 6 years old. At the age of 33, you started learning Mongolian.”

The Qianlong Emperor: “You’re never too old to learn. I conquered Xinjiang and started learning Uyghur at the age of 50. Although I only began to learn Mongolian and Uyghur as an adult, I have become fluent in both. At the age of 66, after conquering Jinchuan in southwestern China, I started learning the local dialect.”

Yongyan: “I remember on your 70th birthday, to welcome the Panchen Lama, you started learning the Tangut language.”

The Qianlong Emperor: “I am no master of the local dialect of Jinchuan or the Tangut language, but every year, when I have an audience with Mongolian, Uyghur, and Jinchuan delegates, I use their languages to greet them. There is no need for interpreters. To develop and maintain good relationships with neighbouring regions, we must never stop learning.”

Yongyan: “I will keep this lesson in mind.”

© The Palace Museum

1009. The Fourth Son Visits His Mother by Peking opera artist Tan Xinpei

Gramophone

© The Palace Museum

The Fourth Son Visits His Mother by Peking opera artist Tan Xinpei

© The Palace Museum

1009. The Fourth Son Visits His Mother by Peking opera artist Tan Xinpei

The Fourth Son Visits His Mother by Peking opera artist Tan Xinpei

© The Palace Museum